Flipping through my backpages

In 1991 I accepted an invitation to write music reviews for Outright! – the politically aware gay monthly magazine for the East Midlands. This was my first official foray into the world of publishing, if you discount my trio of homemade punk rock fanzines, Eat Me, Dispute, and Sniper, which I created when I was fifteen. My dad reproduced these in modest numbers in his work as an industrial photographer, and with intermittent success I attempted to flog my editions to bemused customers in the black depths of the small Virgin store on King Street.

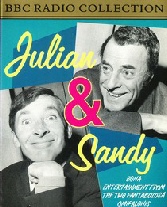

T he initial column space first afforded to me within the pages of Outright! soon increased, and my reviews prompted interesting reactions when I was in the Admiral Duncan pub. One man accused me of betraying my devotion to The Orb; another needed to know why I disliked the second album by The Stone Roses. A third, somewhat older patron applauded me for favourably reviewing the BBC double cassette which complied some of the ‘Round The Horne’ sketches featuring the ‘between jobs’ chorus boys, Julian & Sandy.

he initial column space first afforded to me within the pages of Outright! soon increased, and my reviews prompted interesting reactions when I was in the Admiral Duncan pub. One man accused me of betraying my devotion to The Orb; another needed to know why I disliked the second album by The Stone Roses. A third, somewhat older patron applauded me for favourably reviewing the BBC double cassette which complied some of the ‘Round The Horne’ sketches featuring the ‘between jobs’ chorus boys, Julian & Sandy.

However, an unexpected remark from someone whom I’d known for several years startled me. “Come on, who really writes these articles? It’s not you, because you’re from St. Ann’s – you don’t even know who Zandra Rhodes is.” This casual accusation of my worldly ignorance promptly returned me to the dismissive approach I’d encountered from my teachers at secondary comprehensive school, and reinforced the stigma often attached to being born in a certain area of Nottingham.

My input to Outright! quickly led to an invitation for me to become co-publisher alongside Richard McCance and Chris Richardson. I eagerly agreed, as the autonomous, underground Free Press attitude reminiscent of the hippy and punk eras instinctively appealed to me, and after enrolling on several college courses, I intuitively embraced the burgeoning technological revolution of desk top publishing.

Printed by the independent Anvil Press in Derby, our increasing circulation was funded by advertising from illustrious institutions including local councils and health departments, as well as theatres, independent bookshops, restaurants and cafes, art galleries, gay pubs and clubs. Observational political commentary sat beside literary features and the always engaging free personal ads. We saturated the East Midlands, stretched our circulation to South Yorkshire, and reached out to the conurbations of Cambridgeshire.

Our determination forced us onwards to disseminate information on varied topics including safe sex, HIV/AIDS, human rights, disability rights, abortion options, women’s rights in the workplace, drug and alcohol abuse issues, housing rights, what to do if you are arrested, a comprehensive directory of support facilities and helplines.

Flying in the face of Margaret Thatcher’s hateful, homophobic Clause 28, we rallied against the relentless, rabid fear of queer men generated by main media reportage of the AIDS pandemic. During this period, we witnessed friends, associates, and lovers fatally succumbing to the devastating onslaught of the disease. Unless you were a gay man who lived through that hideous time, you cannot begin to understand the horrors and the homophobic violence engendered by misleading, irresponsible knee-jerk reportage.

V ia what we considered to be rather obvious infiltration (a telephone call asking where and when the meeting was) in 1995 we successfully thwarted a proposed meeting of Islamic Fundamentalist group Hizb ut-Tahrir who advocated the violent murder of homosexuals. We quickly alerted Nottingham City Council that their premises were being rented beneath the cover of an innocuous nom de plume by this dangerous faction in order to spread their toxic ideology. Our intervention resulted in the ban on this group hiring council premises.

ia what we considered to be rather obvious infiltration (a telephone call asking where and when the meeting was) in 1995 we successfully thwarted a proposed meeting of Islamic Fundamentalist group Hizb ut-Tahrir who advocated the violent murder of homosexuals. We quickly alerted Nottingham City Council that their premises were being rented beneath the cover of an innocuous nom de plume by this dangerous faction in order to spread their toxic ideology. Our intervention resulted in the ban on this group hiring council premises.

Outright! was championed by progressive librarians in small mining towns, and welcomed by staff in backwater community centres who were sufficiently emboldened to risk stocking our periodical, thus making it available to those marginalised people who felt trapped within traditional family structures. Outright! provided an assurance of solidarity and the possibility of alternative life choices.

Some libraries reported enraged parents ripping the current issue into shreds, stating that they didn’t want their children subjected to such disgusting stuff, which showed that we must have been doing something right by providing options and reassurances. It also recalled the line from Tom Robinson’s ground-breaking song, Glad To Be Gay: “There’s no nudes in Gay News, our one magazine, but they still found excuses to call it obscene.”

During this frenetic period, I was also responsible for the creation of publicity material for the excellent lesbian hard rock band Atomic Kandy, the decibel-blasting combo bearing absolutely no relation to an insipid girl group with a similar-sounding name who emerged onto the pop charts sometime later. Running parallel was a flirtation of a similar nature for San Francisco queercore quartet Pansy Division, and my ability to talk the hind leg off a donkey was put on hold when I interviewed celebrity DJ Tony de Vit, and Stock, Aitken, Waterman disco diva Lonnie Gordon.

My reportage continued when, for a decade I voluntarily operated an HIV support group for which I was also webmaster, composing all content and graphic identity. The pinnacle of this incredible achievement arose in 2014 when I accepted an award presented by Chris Eyre, the Chief Commissioner of Nottinghamshire Police at a ceremony held in Nottingham’s Council House. Impressed with the independent, user-led approach, in 2015 I was invited to write an article for the quarterly magazine of AIDS Action Europe, Baseline, which eventually ran to 4,000 words covering six pages. Upon publication it appeared that my words ruffled a lot of complacent feathers within professional HIV support circles.

Back to the top of the page

he initial column space first afforded to me within the pages of Outright! soon increased, and my reviews prompted interesting reactions when I was in the Admiral Duncan pub. One man accused me of betraying my devotion to The Orb; another needed to know why I disliked the second album by The Stone Roses. A third, somewhat older patron applauded me for favourably reviewing the BBC double cassette which complied some of the ‘Round The Horne’ sketches featuring the ‘between jobs’ chorus boys, Julian & Sandy.

he initial column space first afforded to me within the pages of Outright! soon increased, and my reviews prompted interesting reactions when I was in the Admiral Duncan pub. One man accused me of betraying my devotion to The Orb; another needed to know why I disliked the second album by The Stone Roses. A third, somewhat older patron applauded me for favourably reviewing the BBC double cassette which complied some of the ‘Round The Horne’ sketches featuring the ‘between jobs’ chorus boys, Julian & Sandy. ia what we considered to be rather obvious infiltration (a telephone call asking where and when the meeting was) in 1995 we successfully thwarted a proposed meeting of Islamic Fundamentalist group Hizb ut-

ia what we considered to be rather obvious infiltration (a telephone call asking where and when the meeting was) in 1995 we successfully thwarted a proposed meeting of Islamic Fundamentalist group Hizb ut-